What Happened to Habbo? Habbo Hotel Turns 25

Habbo Hotel turns 25 this year, marking a chaotic legacy of furniture scams, controversy, internet infamy and unexpected survival. Once a hotspot, it faced near collapse – but it's still online, and still finding ways to reinvent itself for a new generation.

TEXT

Of all the haunted hotels on the internet, Habbo might just be the most iconic. Launched in 2000 by Finnish company Sulake, the isometric hotel tower – half chatroom, half capitalist fever dream – somehow made it to 2025.

That’s 25 years of coded furniture scams, rave rooms, drama, and digital drip. But Habbo at 25 is not the same as Habbo at 15, or even Habbo at 20. It’s a comeback story with jagged edges, equal parts nostalgia bait and cautionary tale. To celebrate the milestone, Habbo’s devs threw a month-long virtual party starting August 15, dropping exclusive furni, animated balloon hats (yes, they move now), and loyalty crowns for the diehard players who have logged in since the early ‘00s. And, yes – some of them really have been here the whole time.

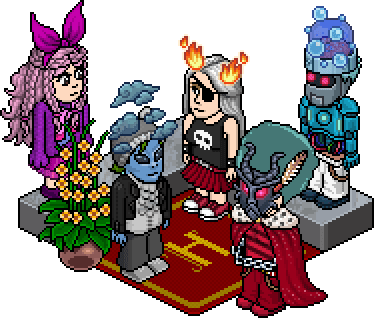

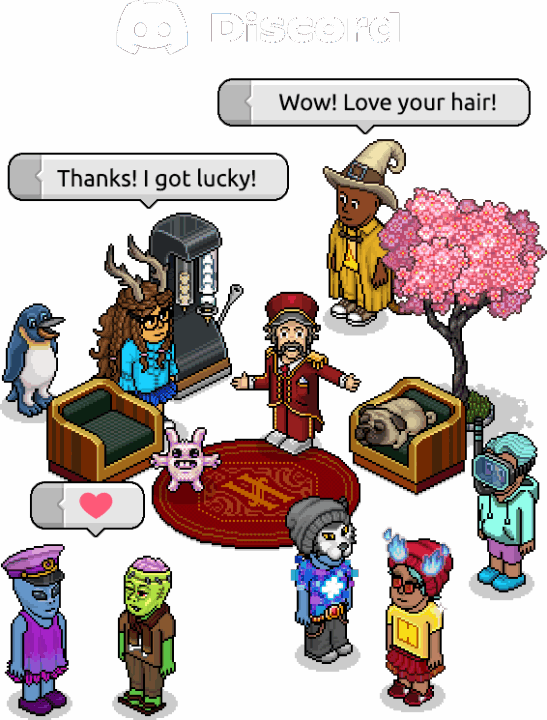

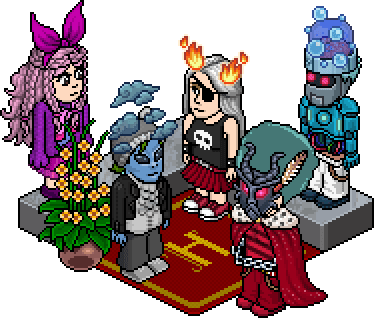

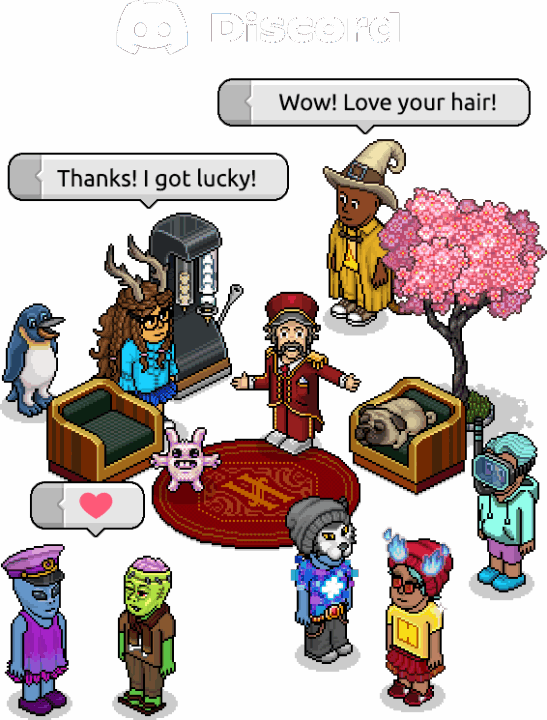

What set Habbo apart from the start wasn’t just the aesthetic, although its lo-fi pixel art and blocky avatars made it instantly recognisable in a sea of early web clunk. It was the agency it gave its users. You didn’t just chat – you built. Hotels became schools, airports, cafés, nightclubs, adoption centres. Teens roleplayed, created games with Wired triggers, and hosted parties that blurred the line between socialising and performance art.

Habbo pioneered what we now call microtransactions, allowing players to buy credits with real-world money and trade them for “furni” – virtual items with their own values, rarities, and status symbols. A single rare could be worth hundreds of credits, and entire black markets emerged outside the game to capitalise on it. Habbo wasn’t just a hotel; it was an early experiment in the gamification of social capital.

But with every pixelated paradise comes a glitch in the matrix. Habbo’s history is laced with controversy, the kind that most games wouldn’t survive. In 2012, UK broadcaster Channel 4 aired an exposé revealing rampant predatory behaviour on the platform, with adults soliciting minors in public rooms. Sulake responded with what players now call “The Great Mute”, cutting off chat across all hotels globally while they reassessed moderation systems. The community backlash was massive, with users submitting stories to a site called “The Great Unmute” in protest. But the scandal exposed a truth that lingered: Habbo’s moderation had never caught up with its popularity. Thousands of teenagers had been navigating a largely unregulated social space dressed as a kids’ game.

That wasn’t the only time Habbo made headlines for all the wrong reasons. In 2007, Dutch police arrested a teenager for stealing around €4,000 worth of virtual furniture by phishing other users’ passwords – a landmark case in the blurry world of digital property law. And in 2006, the platform became ground zero for one of the earliest internet raids to go fully viral. Members of 4chan’s /b/ board created avatars – black avatars, grey suits, afros – and began blocking access to the hotel’s pool, claiming it was “closed due to AIDS”. The action, part protest, part troll campaign, became a meme (“Pools Closed”) and sparked debate over online racism, freedom of expression, and how unprepared online platforms were for coordinated disruption. Habbo was never quite the same after that. It had crossed from a teen hangout to a cultural artefact, one with as much infamy as charm.

Flash forward to 2020, and things nearly collapsed again. Adobe killed off Flash, the tech that powered Habbo’s original client, forcing Sulake to rush out a buggy Unity-based replacement. At the same time, they overhauled the in-game economy, removing peer-to-peer trading, introducing steep taxes, and destabilising item values. Players panicked. Rare items lost thousands in value overnight, and forums lit up with rage and heartbreak. For a platform that built its community on trade and collection, this was the equivalent of economic suicide. Habbo survived, barely – but its userbase thinned, and its reputation tanked.

Yet somehow, in 2025, it’s still here. Still pixelated. Still alive. The 25th anniversary isn’t just a nostalgia trip – it’s a calculated revival effort. Sulake launched “Habbo Hotel: Origins”, a retro-style clone designed to lure back older players craving that 2005 energy. They added animated cosmetics, blockchain-linked collectibles, and exclusive loot systems like the “Collecti-Matic”. Old-school mini-games are back. The “Furni-Matic” lets you recycle junk into new rares. Staff-hosted events and room raids are being spotlighted again. It’s a lot. Some of it works. Some of it doesn’t. But it all points to one thing: Habbo refuses to die.

Not everyone’s convinced. On Reddit, old players call the new features a distraction. “Sulake have lagged behind and abused their insanely loyal playerbase,” one long-time user wrote. Others accuse the company of falling back into old habits: promising transparency, then nerfing the economy anyway. Even Origins – initially celebrated as a purist reboot – has already disappointed some. “They fell straight back into old patterns in a matter of days,” another user said. “Trust is broken.”

So what does Habbo really represent in 2025? For some, it’s a living museum. One of the few surviving digital spaces from the early 2000s. A place where your teen years happened in bedrooms, on clunky desktops, chatting with strangers who felt like best friends. For others, it’s a platform that never evolved, constantly two steps behind its community, making the same mistakes in new pixels. But maybe that’s what makes Habbo so enduring: it’s chaotic, sentimental, impossible to clean up completely. It reflects the messiness of online youth culture better than anything that’s come since. Roblox might have more users, but Habbo has lore.

At 25, Habbo’s still working out what it wants to be. A retro social sim? A blockchain collectibles platform? A party room for burnt-out millennials? Whatever it is, the fact that it still exists – after lawsuits, raids, scandals, and economic crashes – is weirdly impressive. Habbo may not be cool anymore, but it’s still iconic. And sometimes, iconic is enough.

Of all the haunted hotels on the internet, Habbo might just be the most iconic. Launched in 2000 by Finnish company Sulake, the isometric hotel tower – half chatroom, half capitalist fever dream – somehow made it to 2025.

That’s 25 years of coded furniture scams, rave rooms, drama, and digital drip. But Habbo at 25 is not the same as Habbo at 15, or even Habbo at 20. It’s a comeback story with jagged edges, equal parts nostalgia bait and cautionary tale. To celebrate the milestone, Habbo’s devs threw a month-long virtual party starting August 15, dropping exclusive furni, animated balloon hats (yes, they move now), and loyalty crowns for the diehard players who have logged in since the early ‘00s. And, yes – some of them really have been here the whole time.

What set Habbo apart from the start wasn’t just the aesthetic, although its lo-fi pixel art and blocky avatars made it instantly recognisable in a sea of early web clunk. It was the agency it gave its users. You didn’t just chat – you built. Hotels became schools, airports, cafés, nightclubs, adoption centres. Teens roleplayed, created games with Wired triggers, and hosted parties that blurred the line between socialising and performance art.

Habbo pioneered what we now call microtransactions, allowing players to buy credits with real-world money and trade them for “furni” – virtual items with their own values, rarities, and status symbols. A single rare could be worth hundreds of credits, and entire black markets emerged outside the game to capitalise on it. Habbo wasn’t just a hotel; it was an early experiment in the gamification of social capital.

But with every pixelated paradise comes a glitch in the matrix. Habbo’s history is laced with controversy, the kind that most games wouldn’t survive. In 2012, UK broadcaster Channel 4 aired an exposé revealing rampant predatory behaviour on the platform, with adults soliciting minors in public rooms. Sulake responded with what players now call “The Great Mute”, cutting off chat across all hotels globally while they reassessed moderation systems. The community backlash was massive, with users submitting stories to a site called “The Great Unmute” in protest. But the scandal exposed a truth that lingered: Habbo’s moderation had never caught up with its popularity. Thousands of teenagers had been navigating a largely unregulated social space dressed as a kids’ game.

That wasn’t the only time Habbo made headlines for all the wrong reasons. In 2007, Dutch police arrested a teenager for stealing around €4,000 worth of virtual furniture by phishing other users’ passwords – a landmark case in the blurry world of digital property law. And in 2006, the platform became ground zero for one of the earliest internet raids to go fully viral. Members of 4chan’s /b/ board created avatars – black avatars, grey suits, afros – and began blocking access to the hotel’s pool, claiming it was “closed due to AIDS”. The action, part protest, part troll campaign, became a meme (“Pools Closed”) and sparked debate over online racism, freedom of expression, and how unprepared online platforms were for coordinated disruption. Habbo was never quite the same after that. It had crossed from a teen hangout to a cultural artefact, one with as much infamy as charm.

Flash forward to 2020, and things nearly collapsed again. Adobe killed off Flash, the tech that powered Habbo’s original client, forcing Sulake to rush out a buggy Unity-based replacement. At the same time, they overhauled the in-game economy, removing peer-to-peer trading, introducing steep taxes, and destabilising item values. Players panicked. Rare items lost thousands in value overnight, and forums lit up with rage and heartbreak. For a platform that built its community on trade and collection, this was the equivalent of economic suicide. Habbo survived, barely – but its userbase thinned, and its reputation tanked.

Yet somehow, in 2025, it’s still here. Still pixelated. Still alive. The 25th anniversary isn’t just a nostalgia trip – it’s a calculated revival effort. Sulake launched “Habbo Hotel: Origins”, a retro-style clone designed to lure back older players craving that 2005 energy. They added animated cosmetics, blockchain-linked collectibles, and exclusive loot systems like the “Collecti-Matic”. Old-school mini-games are back. The “Furni-Matic” lets you recycle junk into new rares. Staff-hosted events and room raids are being spotlighted again. It’s a lot. Some of it works. Some of it doesn’t. But it all points to one thing: Habbo refuses to die.

Not everyone’s convinced. On Reddit, old players call the new features a distraction. “Sulake have lagged behind and abused their insanely loyal playerbase,” one long-time user wrote. Others accuse the company of falling back into old habits: promising transparency, then nerfing the economy anyway. Even Origins – initially celebrated as a purist reboot – has already disappointed some. “They fell straight back into old patterns in a matter of days,” another user said. “Trust is broken.”

So what does Habbo really represent in 2025? For some, it’s a living museum. One of the few surviving digital spaces from the early 2000s. A place where your teen years happened in bedrooms, on clunky desktops, chatting with strangers who felt like best friends. For others, it’s a platform that never evolved, constantly two steps behind its community, making the same mistakes in new pixels. But maybe that’s what makes Habbo so enduring: it’s chaotic, sentimental, impossible to clean up completely. It reflects the messiness of online youth culture better than anything that’s come since. Roblox might have more users, but Habbo has lore.

At 25, Habbo’s still working out what it wants to be. A retro social sim? A blockchain collectibles platform? A party room for burnt-out millennials? Whatever it is, the fact that it still exists – after lawsuits, raids, scandals, and economic crashes – is weirdly impressive. Habbo may not be cool anymore, but it’s still iconic. And sometimes, iconic is enough.

Enjoyed this story? Support independent gaming and online news by purchasing the latest issue of G.URL. Unlock exclusive content, interviews, and features that celebrate feminine creatives. Get your copy of the physical or digital magazine today!