Why is Gatekeeping Back?

Gatekeeping, once viewed negatively, is experiencing a resurgence as communities strive to maintain the integrity of their cultures. This revival reflects a desire to protect subcultures from dilution, ensuring that new participants engage meaningfully and respect the foundational values that define these communities.

TEXT

In an era of mass accessibility, communities are redefining boundaries to preserve cultural authenticity.

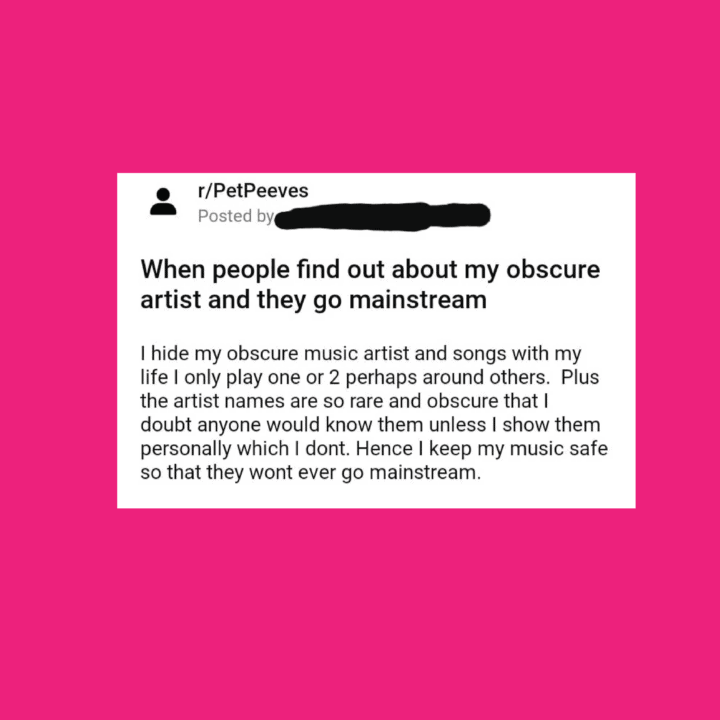

Once the internet’s favourite insult, gatekeeping is experiencing a resurgence. Previously condemned as the antithesis of inclusivity—an elitist tactic to exclude newcomers—it has transformed into a subtle rebellion against ubiquitous accessibility. The mantra “let people enjoy things” has evolved into a more discerning “not everything needs to be for everyone.”

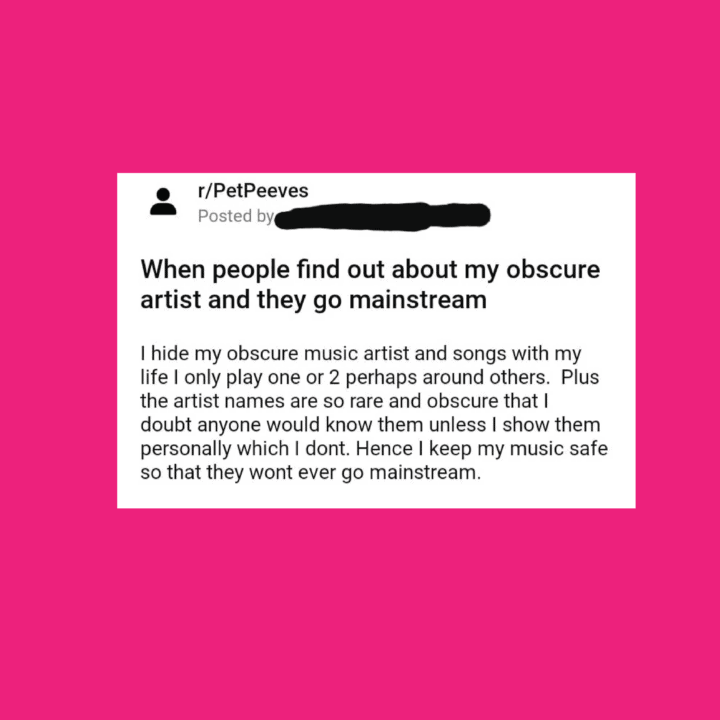

This shift isn’t arbitrary. Over the past decade, the democratisation of culture, propelled by social media, has compressed once-thriving subcultures into ephemeral aesthetic trends. In the UK, this phenomenon is particularly pronounced in fashion and music, industries deeply rooted in working-class communities and underground movements. The indie bands of Camden, once reliant on word-of-mouth, now find themselves at the mercy of TikTok virality. Similarly, the resale culture that flourished in London’s hidden corners—second-hand markets, charity shops, community-run boutiques—is now inundated with Depop resellers and algorithms that render genuine discovery nearly impossible. Consequently, a new wave of gatekeeping has emerged, driven not by superiority but by a desire to preserve something special.

It’s understandable why there’s a backlash against enforced inclusivity. There was a time when uncovering a new artist, brand, or subculture required effort: digging through record stores, participating in forums, attending gigs, engaging with knowledgeable individuals. Now, algorithms deliver content instantaneously, stripping away the rewarding journey of discovery. When niche interests are immediately transformed into content, they lose the personal connection that once made them special. UK rave culture, for example, thrived on word-of-mouth, secret locations, and a sense of collective belonging. Today, as soon as an event gains online traction, it’s sold out to individuals who discovered it through viral clips rather than genuine engagement with the scene. When access becomes too easy, things start to feel disposable.

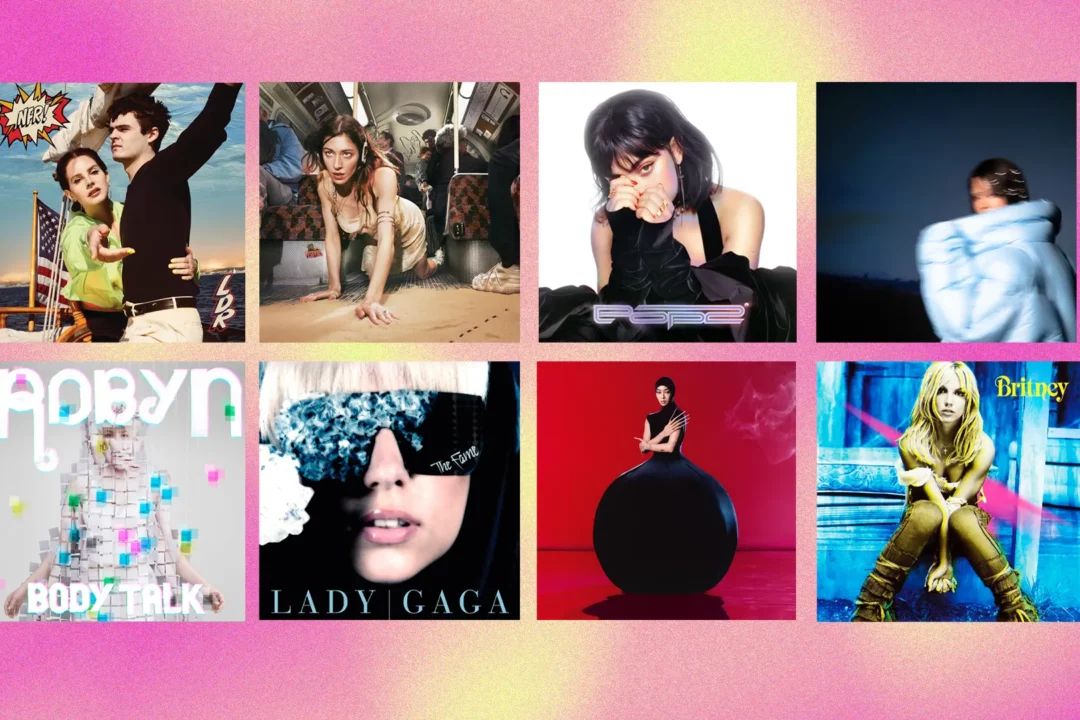

This isn’t about resenting new enthusiasts; the issue lies with transient participants. Those who adopt something because it’s trending, draining a scene of its authenticity before moving on to the next fad. British fashion has always embraced a DIY, community-led ethos—from punk to garage to the rise of independent streetwear brands. However, when these movements’ exclusivity is diluted—when high street retailers mass-produce “underground” aesthetics—their identities erode. The same is occurring in gaming, music, and art. What was once subcultural is now instantly commodified, leaving the original community struggling to retain its essence.

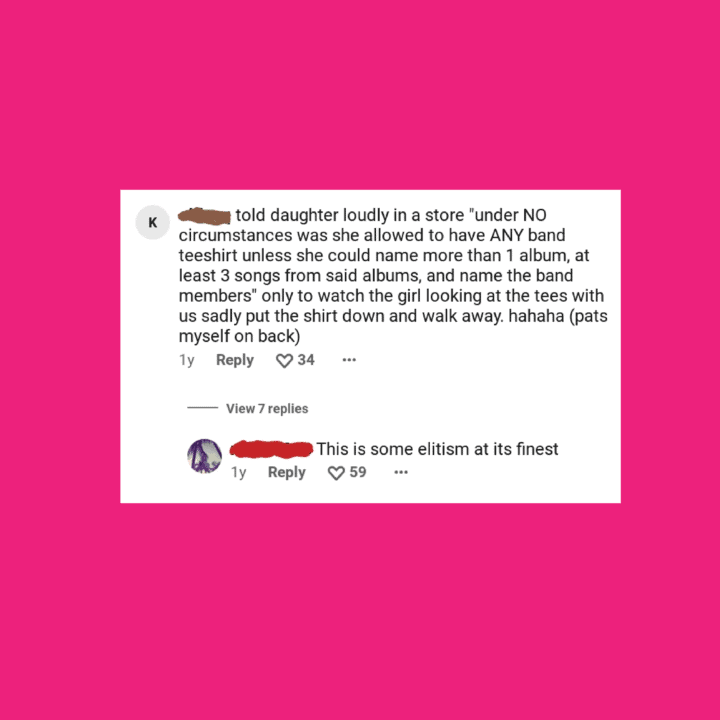

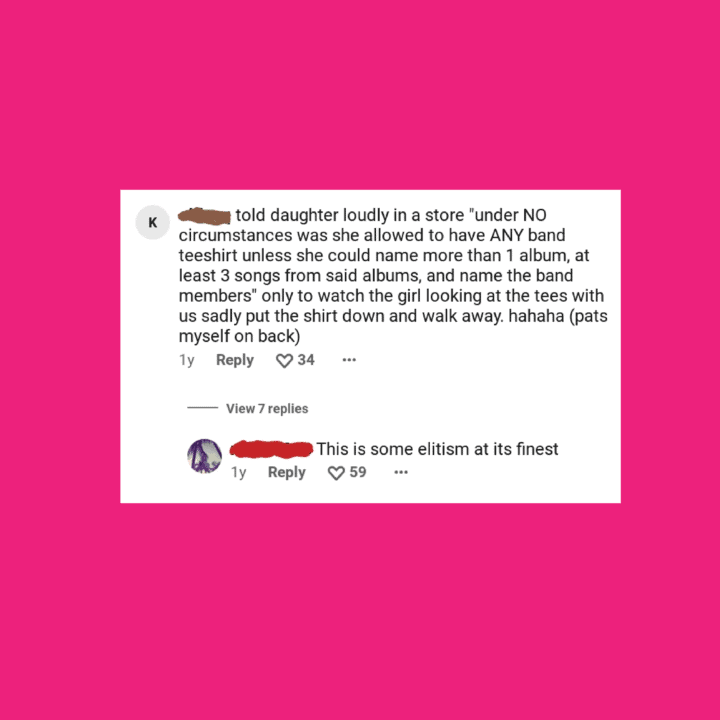

There’s an irony in the anti-gatekeeping movement. The loudest advocates for universal access often inhabit spaces that ridicule individuals for their niche interests. The same internet that demands open doors is quick to mock those who take their passions seriously. The notion that some things should be earned, researched, or deeply engaged with before claiming affiliation has been dismissed as pretentious. Yet, culture is built through dedication, time, and understanding of historical context. The expectation of instant knowledge and universal sharing has led to a cultural superficiality, where engagement is shallow and fleeting.

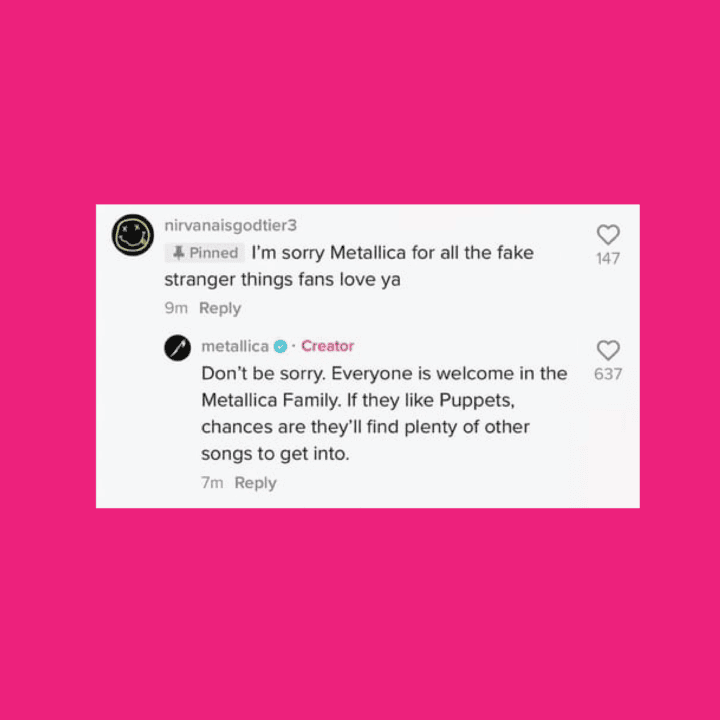

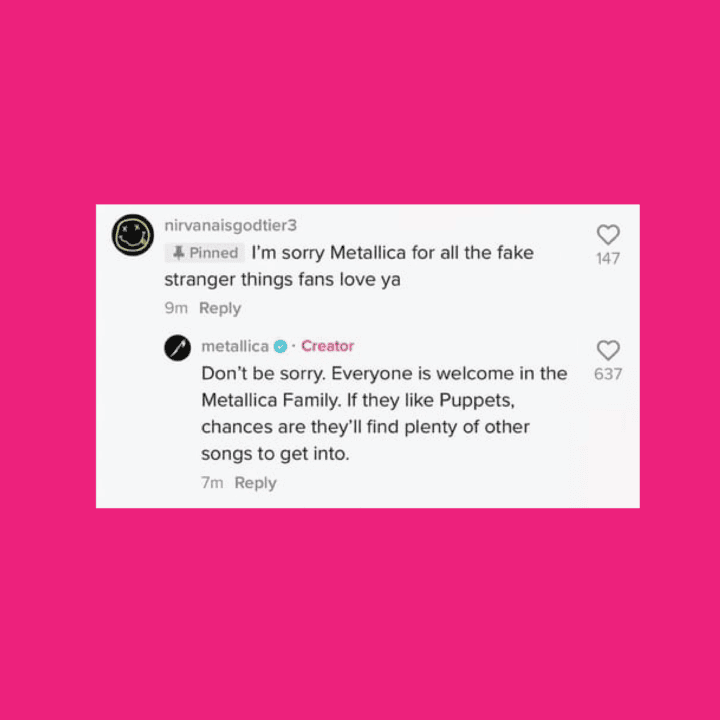

Gatekeeping today isn’t about exclusion for its own sake. It’s a defence mechanism against the algorithmic erosion of culture, aiming to preserve what feels rare and meaningful in an age of mass consumption. It’s not about declaring “you don’t belong here,” but rather asserting, “if you want to be here, invest the effort.” Research the brand before inquiring about someone’s jacket. Listen to a band’s full discography, not just their viral hit. Understand a movement’s context before adopting it as an aesthetic. In an era where everything is up for grabs, there’s value in reserving certain things for those who truly appreciate them.

The resurgence of gatekeeping also reflects a yearning for authenticity and depth in cultural engagement. As subcultures become mainstream and their symbols co-opted, original members often feel a loss of identity and purpose. By setting boundaries, they attempt to protect the integrity of their communities, ensuring that new participants respect and understand the underlying values. This selective sharing fosters genuine connections, allowing cultures to thrive without being diluted by fleeting popularity.

Gatekeeping can sometimes act as a safeguard against the commercialisation of subcultures. When niche movements become more widely known, they may attract commercial interests looking to capitalise on the trend. This commercialisation can change the original dynamics of these movements, often shifting the focus from cultural expression to profit. In some cases, gatekeeping allows communities to maintain a level of control over how their culture is represented and preserved, ensuring that it remains true to its roots.

So, is gatekeeping beneficial? Perhaps its value lies in its necessity, rather than its appeal.

In an era of mass accessibility, communities are redefining boundaries to preserve cultural authenticity.

Once the internet’s favourite insult, gatekeeping is experiencing a resurgence. Previously condemned as the antithesis of inclusivity—an elitist tactic to exclude newcomers—it has transformed into a subtle rebellion against ubiquitous accessibility. The mantra “let people enjoy things” has evolved into a more discerning “not everything needs to be for everyone.”

This shift isn’t arbitrary. Over the past decade, the democratisation of culture, propelled by social media, has compressed once-thriving subcultures into ephemeral aesthetic trends. In the UK, this phenomenon is particularly pronounced in fashion and music, industries deeply rooted in working-class communities and underground movements. The indie bands of Camden, once reliant on word-of-mouth, now find themselves at the mercy of TikTok virality. Similarly, the resale culture that flourished in London’s hidden corners—second-hand markets, charity shops, community-run boutiques—is now inundated with Depop resellers and algorithms that render genuine discovery nearly impossible. Consequently, a new wave of gatekeeping has emerged, driven not by superiority but by a desire to preserve something special.

It’s understandable why there’s a backlash against enforced inclusivity. There was a time when uncovering a new artist, brand, or subculture required effort: digging through record stores, participating in forums, attending gigs, engaging with knowledgeable individuals. Now, algorithms deliver content instantaneously, stripping away the rewarding journey of discovery. When niche interests are immediately transformed into content, they lose the personal connection that once made them special. UK rave culture, for example, thrived on word-of-mouth, secret locations, and a sense of collective belonging. Today, as soon as an event gains online traction, it’s sold out to individuals who discovered it through viral clips rather than genuine engagement with the scene. When access becomes too easy, things start to feel disposable.

This isn’t about resenting new enthusiasts; the issue lies with transient participants. Those who adopt something because it’s trending, draining a scene of its authenticity before moving on to the next fad. British fashion has always embraced a DIY, community-led ethos—from punk to garage to the rise of independent streetwear brands. However, when these movements’ exclusivity is diluted—when high street retailers mass-produce “underground” aesthetics—their identities erode. The same is occurring in gaming, music, and art. What was once subcultural is now instantly commodified, leaving the original community struggling to retain its essence.

There’s an irony in the anti-gatekeeping movement. The loudest advocates for universal access often inhabit spaces that ridicule individuals for their niche interests. The same internet that demands open doors is quick to mock those who take their passions seriously. The notion that some things should be earned, researched, or deeply engaged with before claiming affiliation has been dismissed as pretentious. Yet, culture is built through dedication, time, and understanding of historical context. The expectation of instant knowledge and universal sharing has led to a cultural superficiality, where engagement is shallow and fleeting.

Gatekeeping today isn’t about exclusion for its own sake. It’s a defence mechanism against the algorithmic erosion of culture, aiming to preserve what feels rare and meaningful in an age of mass consumption. It’s not about declaring “you don’t belong here,” but rather asserting, “if you want to be here, invest the effort.” Research the brand before inquiring about someone’s jacket. Listen to a band’s full discography, not just their viral hit. Understand a movement’s context before adopting it as an aesthetic. In an era where everything is up for grabs, there’s value in reserving certain things for those who truly appreciate them.

The resurgence of gatekeeping also reflects a yearning for authenticity and depth in cultural engagement. As subcultures become mainstream and their symbols co-opted, original members often feel a loss of identity and purpose. By setting boundaries, they attempt to protect the integrity of their communities, ensuring that new participants respect and understand the underlying values. This selective sharing fosters genuine connections, allowing cultures to thrive without being diluted by fleeting popularity.

Gatekeeping can sometimes act as a safeguard against the commercialisation of subcultures. When niche movements become more widely known, they may attract commercial interests looking to capitalise on the trend. This commercialisation can change the original dynamics of these movements, often shifting the focus from cultural expression to profit. In some cases, gatekeeping allows communities to maintain a level of control over how their culture is represented and preserved, ensuring that it remains true to its roots.

So, is gatekeeping beneficial? Perhaps its value lies in its necessity, rather than its appeal.

Enjoyed this story? Support independent gaming and online news by purchasing the latest issue of G.URL. Unlock exclusive content, interviews, and features that celebrate feminine creatives. Get your copy of the physical or digital magazine today!